Locale

What are the people like? What were they like? Who lived in this neighborhood? Were there patterns related to things like ethnicity, race, class, or occupation? What is it about the population of the area that reveals something about the neighborhood? In the 1910s, how many residents of the blocks in Jackson’s Hollow near the Brooklyn Navy Yard worked maritime jobs? What Spanish-speaking populations inhabit the neighborhood of Spanish Harlem? Researching present-day Chinatown, how much of it sixty years ago was Little Italy? Or even twenty years ago? Why was there a high population of African-Americans in the area north of West 59th Street in 1920, where Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts is located today? Researching the people of a neighborhood reveals the social history of the locale.

What are the people like? What were they like? Who lived in this neighborhood? Were there patterns related to things like ethnicity, race, class, or occupation? What is it about the population of the area that reveals something about the neighborhood? In the 1910s, how many residents of the blocks in Jackson’s Hollow near the Brooklyn Navy Yard worked maritime jobs? What Spanish-speaking populations inhabit the neighborhood of Spanish Harlem? Researching present-day Chinatown, how much of it sixty years ago was Little Italy? Or even twenty years ago? Why was there a high population of African-Americans in the area north of West 59th Street in 1920, where Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts is located today? Researching the people of a neighborhood reveals the social history of the locale.

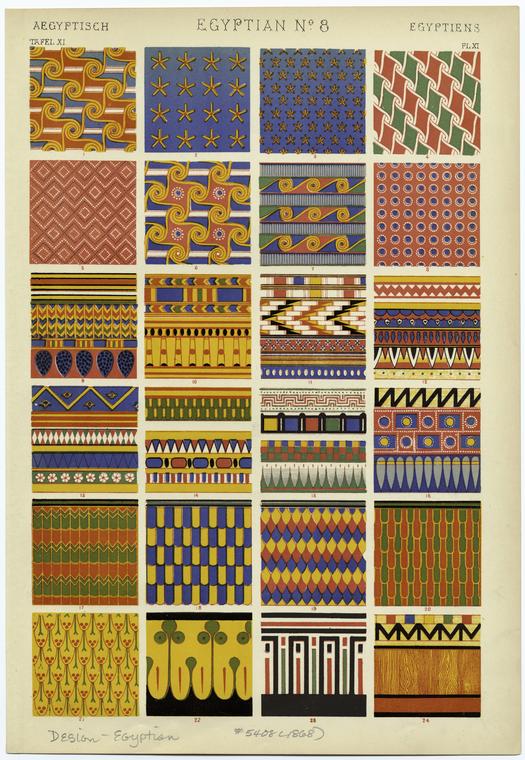

What does it look like? What did it look like? At the reference desk, images are one of the most sought after resources in neighborhood research. Photographs might communicate extra dimensions of an area that are not conveyed through nonvisual materials. They also provide a vivid sense of immediacy to the past, as if crossing through the wormhole. Images of the built environment and street life enable a more intimate and possibly more profound understanding of a place.

Towns and cities change. New York City is one of the most changing cities on the planet. “To live is to change,” said playwright Tennessee Williams, “to change is to live.” When exploring the history of a neighborhood, “that used to be a…” and “that’s where the old whatever used to be” are inevitable entry points to the narrative of a site. How do you find out what “used to be there?”

Towns and cities change. New York City is one of the most changing cities on the planet. “To live is to change,” said playwright Tennessee Williams, “to change is to live.” When exploring the history of a neighborhood, “that used to be a…” and “that’s where the old whatever used to be” are inevitable entry points to the narrative of a site. How do you find out what “used to be there?”

At the other end of the spectrum - take a look at what is still there, even after all those years. The Bridge Cafe at 279 Water Street is sadly no longer in operation, but the building itself supposedly dates to 1794, and still appears as if behind the upstairs windows live oystermen and sailmakers. Or, sure, Times Square has been the entertainment district for over 100 years, but the changes in the neighborhood surpass the size of crowds on New Years Eve.

Also, the tour was simply the narrative form: this idea applies to whatever form your research ultimately takes (article, book, exhibit, etc.).

Another pattern might be statues - the statues themselves are the pattern, the art form and mode of representation - which then serves the opportunity to note connections or associations between whatever they may represent.

Patterns, connections, and associations are there. Find them.

One of the most common factoids for any neighborhood is “the oldest” of something. Though any superlative about an area may seem to serve its own purpose as notable, it often will not stand on its own as conveying much about the locale, nor sustain much unique interest without context. For example, If the oldest building in the neighborhood was built in 1975, and not 1875, such a fact should prompt other aspects of the area. “That up there is the most expensive apartment in town.” So what? Who lives there? How much? Why did the pad go for so much mazuma? For “oldest,” you are researching exact dates, time frames, date ranges, and cross-referencing where these claims are being made. Round things out and support a singular bare fact with some sinew and heartbeat.

One of the most common factoids for any neighborhood is “the oldest” of something. Though any superlative about an area may seem to serve its own purpose as notable, it often will not stand on its own as conveying much about the locale, nor sustain much unique interest without context. For example, If the oldest building in the neighborhood was built in 1975, and not 1875, such a fact should prompt other aspects of the area. “That up there is the most expensive apartment in town.” So what? Who lives there? How much? Why did the pad go for so much mazuma? For “oldest,” you are researching exact dates, time frames, date ranges, and cross-referencing where these claims are being made. Round things out and support a singular bare fact with some sinew and heartbeat.