Live Albums, the Machine, and Metal Machine

The last show of the Berlin tour, on December 21, 1973 at the Palladium (then called the Academy of Music), East 14th Street, Manhattan, was recorded and released in February 1974 as Rock 'N' Roll Animal. The first live album of Lou Reed's solo career, it sold better than even Transformer had and receives high praise to this day. In fact it's Reed's first release to receive a gold certification from the RIAA - a feat that he would not come close to for another 15 years. This established a formula for record labels as a sure-fire way to leverage Reed's fan base. When Berlin's follow-up Sally Can't Dance (1974) was released to middling reviews and RCA concluded that Lou Reed was taking too long to record his next album, the label released the rest of the December 1973 concert as Lou Reed Live in March 1975. Lou Reed Live in essence consisted of offcuts from Rock N Roll Animal and since it was already recorded material Reed had little to do with the final project.

This is the climate in which, four months later, Lou Reed released the most contentious album of his entire musical career - Metal Machine Music (1975).

When Metal Machine Music was released in July 1975 it was not what anyone, including the record executives at RCA, had expected. Dressed in a distinctly Rock & Roll cover, it is a 64:11 (or infinitely) long love letter to Drone Music. Commonly categorized as Electronic Noise music, the album is a two LP recording of feedback and guitar pedal effects, with no melody, rhythm, lyrics, or any recognizable compositional structure. As such it is more akin to an experimental classical music release, a la La Monte Young and his Theatre of Eternal Music, than the Lou Reed of yesteryear. The record even had a locking groove, meaning that instead of the record player needle tracking to the end of the disc and stop playing, it would instead track into a single groove over and over and play the same single-rotation's worth of audio on repeated until the needle was lifted.

Label execs, critics and Reed's fans didn't know what to do with it.  For the execs it was a last straw, Reed's next album would be released on Arista Records. For most critics it was at minimum indulgent and uninspired, and at worst it was viewed as an insult directed at them personally. Lester Bangs in the February 1976 issue of Creem had a 4 page piece about it with the headline "How To Succeed In Torture Without Really Trying Or, Louie Come Home, All is Forgiven".

For the execs it was a last straw, Reed's next album would be released on Arista Records. For most critics it was at minimum indulgent and uninspired, and at worst it was viewed as an insult directed at them personally. Lester Bangs in the February 1976 issue of Creem had a 4 page piece about it with the headline "How To Succeed In Torture Without Really Trying Or, Louie Come Home, All is Forgiven".

For fans, of the purportedly 100,000 copies that sold (a very respectable number), so many were returned that it was pulled from shelves. To those expecting the next Sally Can't Dance, it simply wasn't clear whether the record played correctly or not. For Lou Reed, however, it was something of a return to basics - to a style that he, John Cale, and the early Velvet Underground had explored 10 years earlier - and to a musical technique he would sporadically return to again and again for the rest of his life.

Lou Reed's copy of Metal Machine Music

(Lou Reed Papers)

Putting Myths & Murmers To Rest

We know that Lou Reed's 1975 studio album Metal Machine Music was contentious, with people manifesting targets of Reed's ire in every direction. The situation was exasperated, perhaps even created, by Reed's own caustic and sarcastic sense of humor and his notorious difficulty putting up with people he didn't take seriously - namely journalists. Consequently, this album generated a bevy of myths surrounding it.

The spite album

The spite album

The most oft repeated one is that Reed churned it out with no effort for the sole purpose of breaking his contract with RCA. He refuted this all his life, naturally, but seeing how RCA released Lou Reed Live using nothing but offcuts from the Rock N Roll Animal recordings, it's understandable that Reed would have been dissatisfied with management. However, he has never hidden his desire for his music to be listened to, and for commercial success. In 1984 Lou Reed told Sue Simmons on New York's News 4 Live at Five:

I don't make these records to stack in my closet so I can look at them. You know? Look there's my 17th record sitting on top of my 16th record un-played by the world...

As for the question of effort - the Lou Reed Papers contains a ¼” open reel tape box labeled “Electric Rock Symphony, Part 1” and is an unmistakable demo for Metal Machine Music (1975). Originally thought to be from 1974-1975, thanks to their work curating the Lou Reed exhibit on display at LPA until March 2023, Don Fleming and Jason Stern recently discovered this tape is actually from 1965-1966. Situating it nearly 10 years prior to Metal Machine Music lends credence to the idea that the album composition was considered and crafted. Another thing to consider is the presence of droning and guitar feedback manipulation in Reed's music heard throughout the decade prior - from "The Ostrich" during his Pickwick years and carrying through his entire collaboration with John Cale. At very least, if he came to it spitefully, he came by it honestly.

Throwing the game

Another myth is that RCA wanted Metal Machine Music to be released on it's classical music imprint Red Label. The idea is that RCA hoped to more accurately portray the albums contents as modern classical or experimental as apposed to Popular or Rock, but Lou Reed refused just to spite them. This and the opposite - that Reed wanted it on Red Label for the aforementioned reason but RCA refused because it would limit the market too much - have both been published in authoritative biographies. Fortunately, in the Lou Reed Papers we have recordings of Reed discussing this exact thing later in life. In April 2006 he explained:

The record company, and me too, were worried that people who liked "Walk on the Wild Side" would see this and buy it and it was the opposite. Not really - to me it's not the opposite. But they probably wanted songs and a voice and we wanted to let them know that it was all electronic music. So the idea of saying it was an Electronic and Musical Composition was to try to tell people that there was no vocals, no songs.

I brought it to the classical label to put out. But then I made it have a Rock and Roll cover and that was the beginning of the end.

Perhaps the best judge of these myths is the fact that Lou Reed never abandoned either the album or the drone technique. There was no touring of the album in the '70s, no live performances or marketing blitz, but 25 years later Metal Machine Music, the droning, the guitar feedback, and the definition-bending experimentation would resurface and underlay the remainder of his career.

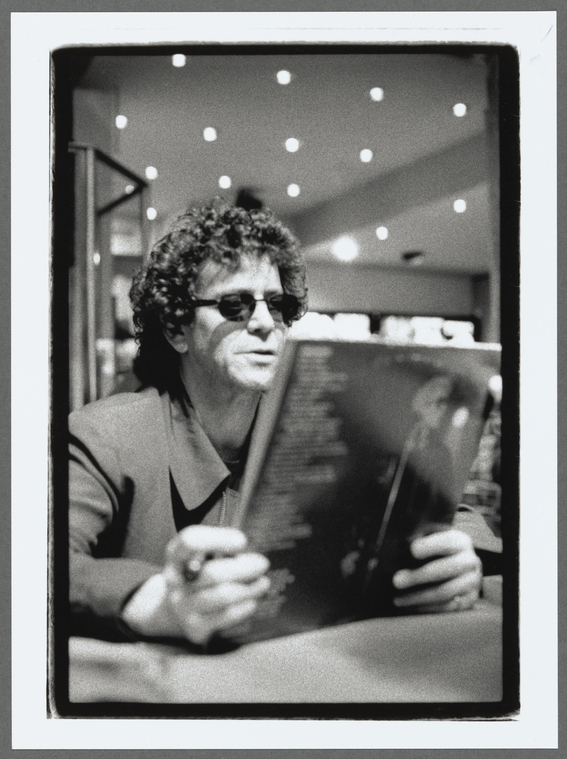

Lou Reed with Metal Machine Music at a signing, Paris, 1996

(Lou Reed Papers)