VU Post Lou

Where had all the Velvets Gone?

Lou Reed's decades-long solo career, his collected Lou Reed Papers, and this guide (specifically starting with the Poetry section) are evidence enough of what Reed did after he left the Velvet Underground.

VU Post Lou

After Lou Reed left the Velvets Underground in August 1970, the group continued without him for a time, finishing the Loaded (1970) tours in the US and in Europe the following year, in releasing one last studio album. Purportedly manager Steve Sesnick pushed Doug Yule to be the leader of the group, situating Yule as a complete replacement for Reed. Despite Sesnick's machinations, the band stayed together until the next August when Sterling Morrison, the last of the founding members, quit the group. With Morrison's departure Atlantic Records, who had been waiting on a final studio album from the group, decided to cut their loses and release the Live at Max's Kansas City (1972), which was mastered from audience recorded tapes from two years prior while Lou Reed was still with the group. This left Moe Tucker as the sole representative of the "classic" Velvet Underground line up.

After Lou Reed left the Velvets Underground in August 1970, the group continued without him for a time, finishing the Loaded (1970) tours in the US and in Europe the following year, in releasing one last studio album. Purportedly manager Steve Sesnick pushed Doug Yule to be the leader of the group, situating Yule as a complete replacement for Reed. Despite Sesnick's machinations, the band stayed together until the next August when Sterling Morrison, the last of the founding members, quit the group. With Morrison's departure Atlantic Records, who had been waiting on a final studio album from the group, decided to cut their loses and release the Live at Max's Kansas City (1972), which was mastered from audience recorded tapes from two years prior while Lou Reed was still with the group. This left Moe Tucker as the sole representative of the "classic" Velvet Underground line up.

Above is Lou Reed's personal copy of Squeeze (1973) (Lou Reed Collection of Published Media).

The group that Lou Reed had fought John Cale for the reigns of and which he had both co-founded and, for all intents and purposes, lead for 2 years, had taken on a life of it's own. For it's last 3 years the Velvet Underground had become completely divorced from Lou Reed, and the story is usually told that Reed had grown to distrust Doug Yule once Sesnick put him in charge. What might come as a surprise, then, is that in Spring 1974, just about a year after the Velvet Underground had been unceremoniously dissolved, Reed invited Yule to record with him on Sally Can't Dance (1974). Yule contributed bass on "Billy", the last track of the album, amongst other later released songs. More notably, however, is that Reed invited Yule to join his touring band for his 1975 world tour.

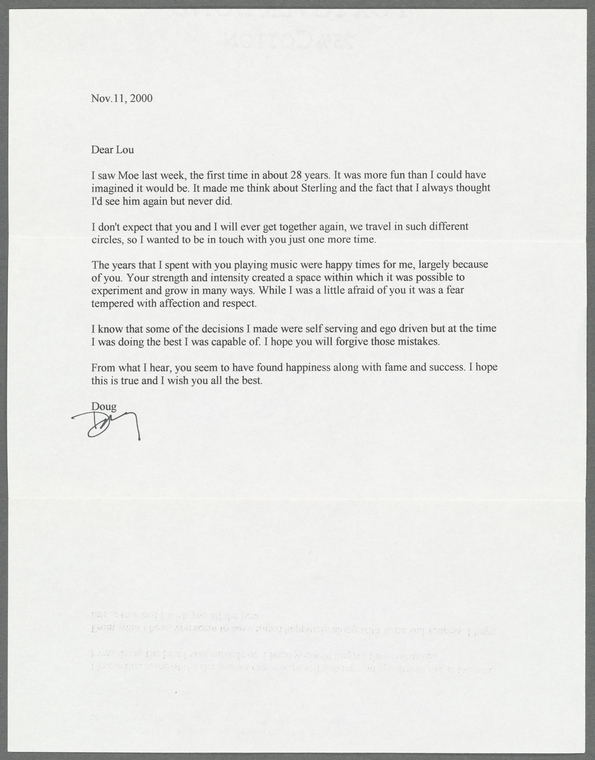

One thing we do know for certain is that Doug Yule and Lou Reed went their separate ways after 1975, never working together again. A gem in the Lou Reed Papers is this letter written November 11, 2000 addressed from Doug Yule to Lou Reed. It offers insight into Yule's perspective on this time.

And the Rest of the Classics?

Sterling Morrison, the next to leave after Reed, had already begun his graduate studies at Liberty Hall in Houston, Texas. When it was time for the group to return to New York, he stayed behind and settled down, largely leaving professional music behind. Famously in the mid '70s he would sign onto a Houston tugboat as a deckhand and by the '80s he had worked his way up to a captainship which he would hold through the decade.

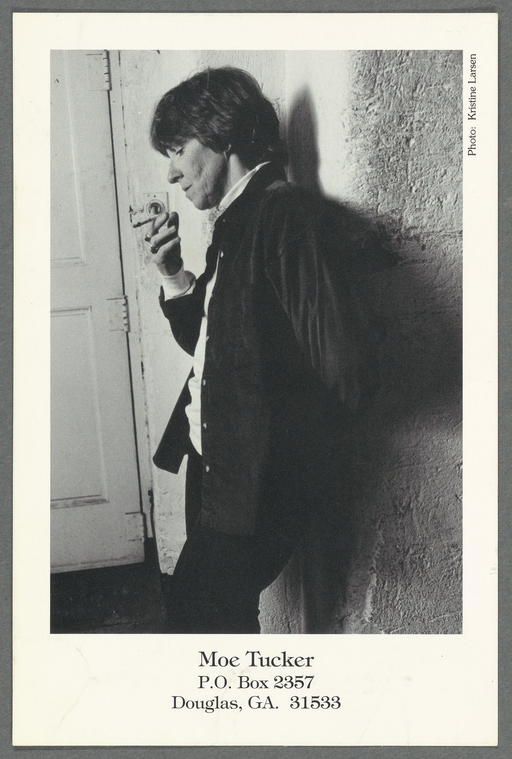

Moe Tucker spent her first post-Velvet Underground decade away from music and raising her family. Starting in 1982, however, she released her first solo album Playin' Possum (1982), which was recorded in her living room and has her playing every instrument. She restarted her musical career in earnest in 1988 by recording, over the better part of the year, her second album Life in Exile After Abdication (1989) which would feature a veritable who's who of the '80s indie rock world, in addition to Lou Reed. (Just a note from this guides author: on track number 7, Tucker's cover of the Velvet Underground classic "Pale Blue Eyes", features backing vocals by Don Fleming, Lou Reed Archive's archivist and co-curators of the NYPL LPA's exhibit "Lou Reed: Caught Between The Twisted Stars", who was at the time a musician in the Velvet Monkeys and hadn't yet started a long career in music production.)

Lastly, and giving Lou Reed a run for his money for being the busiest of Velvet Underground alumni, is John Cale.

Following his split from the band in 1968 John Cale began recording the first of what would become a long line of notable and successful solo and collaboration albums. Starting with Vintage Violence (1970), and continuing to this day, Cale would step in and out of the myriad genres that so clearly played a part in his collaborations with Lou Reed - Rock, Art Rock, Baroque Pop, Modern Classical, Experimental Rock, and Proto-Punk. Not only known as a classically trained multi-instrumentalist and composer, he would go onto produce some of the most notable albums of the Rock era such as:

- The Stooges (1969) by The Stooges

- The Marble Index (1968) by Nico

- Horses (1975) by Patti Smith

- The Modern Lovers (1976) by The Modern Lovers

Moe Tucker card to Lou Reed, front

(Lou Reed Papers)

Moe Tucker card to Lou Reed, back

(Lou Reed Papers)

The Post-Drella World

Warhol's Lasting Shadow

An often disregarded partner in the Velvet Underground's debut success, Velvet Underground & Nico (1967), was Andy Warhol. While his artistic voice only immediately appears in the cover art, designs that the Velvet Underground, Lou Reed, and John Cale would welcome again later on, Warhol's artistic choices speak volumes in crafting the sound of the group. From the very start of the band's career, Andy Warhol appears to have been necessary for their successes. Their step from a gig band to a touring group was organized, funded, and often times hosted by Andy Warhol and the Factory. Their signing to a record label - Verve - had purportedly all to do with Andy Warhol's name brand guarantee and little to do with the groups unique music or oft-forgotten studio experience. Lastly, the album that was finally cut was embattled from the start by studio engineers all the way up to Verve executives, yet was defended and insulated by Warhol. In 1967, in a world where The Velvet Underground & Nico had yet to be heard, their sound was a deal breaker.

Thanks to Warhol, per Brian Eno's famous quote, the 30,000 buyers of the album were able to start their 30,000 bands and the rest is history. Any less commitment from Warhol and the album either wouldn't exist or its sound would be much more marketable and probably less influential. The Velvet Underground all recognized Warhol's influence on their success.

For Lou Reed, Warhol became a major figure in his life.

The Warhol Manuscript and the Demo

The Philosophy of Andy Warhol by The private Andy Warhol talks: about love, sex, food, beauty, fame, work, money, success; about New York and America; and about himself--his childhood in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, good times and bad times in the Big Apple, the explosion of his career in the sixties, and life among celebrities.

Call Number: [eNYPL Book]ISBN: 0151890501Publication Date: 1975-09-01

In the Lou Reed Papers we have a manuscript of Andy Warhol’s book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again), published 1975 by Harcourt, that was sent to Lou Reed prior to printing.

Not only does this serve as an artifact of their ongoing relationship after the rollercoaster that was their professional relationship, but it also is the pages that influenced Lou Reed to write and record 12 never-released songs that researchers have only recently uncovered.

In 2019 Cornell University musicologist Judith Peraino was studying the culture surrounding mixtapes and working through the hundreds of tapes in the Andy Warhol Museum and found particular cassette labeled "Philosophy Songs (From A to B & Back)". It proved to contain 12 never-released Lou Reed songs. One side of the tape consisted of live recordings of songs heard on Reed's solo albums Sally Can't Dance (1974) and Coney Island Baby (1976), but the other side contained 12 recordings Reed made in his Manhattan apartment and which can't be found anywhere else... Except for in the Lou Reed Papers.

At least two of the songs can be heard in a tape that we have in the Lou Reed Papers. The A side of the cassette tape labeled "Lou Reed [Demos/Recorded Conversation and "Wild Angel" by Nelson Slater]" starts with four tracks, including two that are assumed to be a demo of the song Peraino labeled "So What" and one track assumed to be a demo of what Peraino labeled "Success". This side was recorded over One of These Nights by The Eagles.

Judith Peraino published her findings in the Journal of Musicology in an article entitled I’ll Be Your Mixtape: Lou Reed, Andy Warhol, and the Queer Intimacies of Cassettes. In an interview with the Cornell Chronicle, Peraino explained what she found so remarkable about the tape she uncovered at The Andy Warhol Museum:

It was an example of Lou Reed curating himself, putting together a kind of ideal setlist for Andy Warhol. I see the message of this tape as being both courtship and breakup. The one side is saying "look at me, and what I've been able to do this year, [and the other side is saying] now look at you".