Kwame Nkrumah Biography

Kwame Nkrumah was the first prime minister of Ghana (former British Gold Coast colony and British Togoland) at independence in 1957. He later became the first president of Ghana as a Republic in 1960. Nkrumah was born in the village of Nkroful in Nzima Land, an area Southwest of the Gold Coast colony. As was common in those days, keeping official records of births was not mandatory, as a result, Nkrumah’s exact date of birth is open to question. For official purposes, he used September 21, 1902, as his date of birth, recorded by the Roman Catholic Church priest who baptized him. However, Nkrumah later calculated Saturday, September 18, 1909, as the most likely date of his birth.

As was common in traditional Africa, Nkrumah was born in a polygamous family setting where his father, Kofi Ngonloma, from the Akan tribe and a goldsmith by profession, had many wives and children. His mother, Elizabeth Nyaniba, was a retail trader, and Nkrumah was her only child. At birth, his father named him Nwia Kofi and was later baptized, Francis. As was the tradition of the Akan, Nkrumah also had a name after the day of his birth, Kwame, for Saturday. Throughout his career, Nkrumah had used all these forenames interchangeably, but Kwame undoubtedly became the most popular name.

Early in his life, Nkrumah’s mother strongly insisted that he start his formal education. His father supported the idea and Nkrumah was sent to a local elementary school operated by a Roman Catholic mission. He disliked school initially but eventually developed an interest and started enjoying his lessons to the point he was always looking forward to being in school. He did well at school and became a pupil-teacher after eight years in elementary school. Nkrumah’s performance as a pupil-teacher was quite impressive. Thus, in 1926, he was sent to train at the Government Training College that later became the Achimota College in Accra, the present-day capital city of Ghana. He graduated from Achimota in 1930 and became a teacher at a Roman Catholic primary school in Elmina. He soon moved on to take up a headmaster position at another Roman Catholic school in the coastal town of Axim. Later on, Nkrumah also taught at a Catholic seminary at Amissano and even considered priesthood as a career.

Nkrumah developed a strong interest in traveling abroad to Britain to further his education. At that time, he was exposed to the political and Pan-Africanist ideologies of influential activists like W.E.B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey. Somehow, he ended up at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, United States of America, under a small scholarship. These were financially challenging times for Nkrumah, and he had to pick up some menial and uncomfortable jobs to support himself and supplement his grant. These jobs include buying fish at wholesale price and selling them on an open street corner in Harlem, New York, for meager profits, and many times at a financial loss. He soon developed skin rashes due to allergies to fish and had to abandon the unprofitable fish trade to work at a soap factory which he found even more challenging. Despite the difficulties, Nkrumah graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in economics and sociology from Lincoln in 1939. He enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania and obtained a Master of Science in philosophy and education. In 1942, he started a Ph.D. research program but never completed it. At this point, Nkrumah already had close interactions with some African student groups with radical political ideologies geared mainly toward anti-imperialism and struggles for the colonial emancipation of Africa. The African Students Association was such a group of which he was elected president. Nkrumah was deeply influenced by radical ideologies, some of which were communist.

In 1945, after ten difficult years in the United States, Nkrumah left to continue his studies in Britain. His interest was to study law in London while working to complete his thesis for a doctorate in philosophy. By then, Nkrumah’s political and ideological experiences in the United States had already turned him into a committed radical nationalist, and it was not long before he found himself tangled up with political activities in London. He associated with the Communist Party of England and soon joined the West African Students’ Union, a radical group of which he later became the vice president. In 1962, Nkrumah expressed the political and philosophical ideas he immersed over the years in his first major publication, Towards Colonial Freedom – a restatement of imperialism as presented by Lenin of the Soviet Union.

In 1947, Nkrumah left Britain and returned home to Gold Coast to join the newly formed moderate nationalist party, the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), of which he became the general secretary. As general secretary, he had the opportunity to organize and address numerous meetings across the colony. He soon gained popularity and created a mass base for the party. Nkrumah had a radical approach to political activism against the British colonial government, and it was no surprise that when mass riots broke out across the colony in 1948, he was arrested together with other leaders of the UGCC under suspicion of incitement.

Nkrumah left the moderate UGCC party in 1949 to form the more radical Convention People’s Party (CPP), which soon became a mass-based party of radical supporters and anti-colonial activists. Although he ushered in a campaign of “positive action – nonviolent protests”, extensive mass protests soon broke out against the British colonial authorities and Nkrumah was arrested again and sent to prison for a year. While he was in prison, the mass support for the CPP never faded and the party swept the polls in Gold Coast’s first general election held in February 1951. Nkrumah won a parliamentary seat and was released from prison. That was the beginning of a close relationship that developed between him and the colonial governor, Sir Charles Arden-Clarke. Nkrumah later served as leader of government business and soon after, prime minister of Gold Coast colony in 1952. He continued to put intense political pressure on the British colonial administration to gain the colony's independence. His efforts finally paid off, and in 1957, when Gold Coast and British Togoland territory merged under the British Commonwealth as independent Ghana, Nkrumah became the first prime minister of the newly formed independent state. Thereby, under his brilliant political leadership and legendary strategic influence, Gold Coast became the first black African colony to be liberated from British rule, setting the trend for other colonies on the continent to follow.

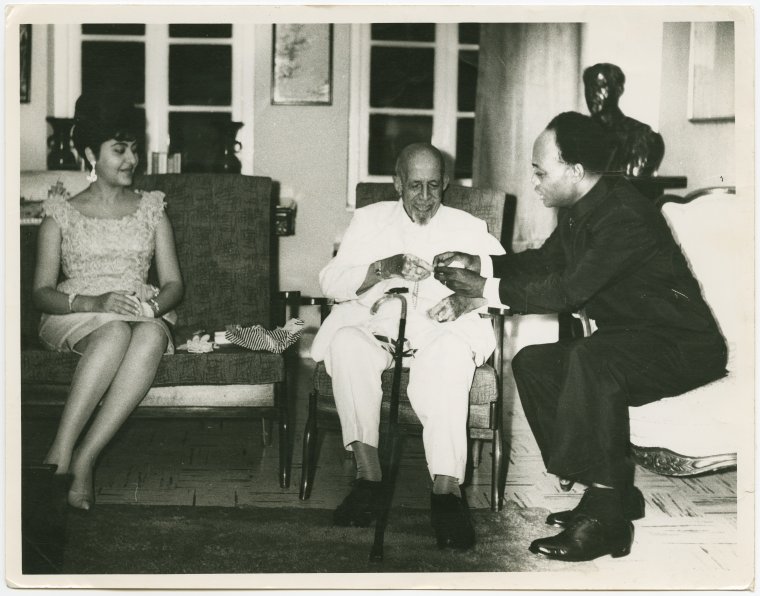

In 1960, Nkrumah became Ghana’s first president as a republic, and by 1961, he nationalized the major agricultural export trade of the country – the cocoa trade. He focused on industrialization, introduced socialist policies, and was instrumental in establishing the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, an attempt to foster the unity of the African continent. Nkrumah also prioritized education, and in 1964, he secured a yearlong service of Jean Blackwell Hutson (librarian and curator of the Schomburg Collection 1948-1972; chief of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture 1972-1980; namesake for the Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division) to build an Africana collection for the University of Ghana. Nkrumah was a patron at the former 135th St.branch of the New York Public Library when he was in Harlem, New York City.

Despite the progress he made on the political, social, economic, and educational fronts for Ghana in particular and the African continent at large, Nkrumah’s government manifested some dictatorial characteristics, including legalizing the arrest and imprisonment without trial of anyone believed to be a security risk to his administration. Opposition to his government grew and he survived at least two serious assassination attempts over the years. Eventually, while out of the country on a peacemaking mission in Vietnam, Nkrumah was overthrown by a military coup on February 24, 1966. He went into exile in Guinea where he lived and continued to write and carried on the African revolutionary struggle for years, under the protection of president Sekou Toure. Nkrumah eventually fell very ill and died of cancer at a hospital in Bucharest, Romania on April 27, 1972. He was first buried in Guinea and later moved to his hometown of Nkroful, Southwestern Ghana. In 1992, his body was moved again and reburied at his final resting place in Accra. Nkrumah is widely remembered and celebrated as an iconic symbol and pioneer of the Pan-African struggles for the liberation of Africa.